Alan Lumsden – a personal memoir

I first met Alan outside a tube station in north London one morning in November 1971. I was 25, so he must have been 37 or 38. We were to appear as court musicians in the film Henry VIII and his Six Wives and Alan had offered to give the new member of the group a lift to the film studios at Elstree. Or possibly Shepperton. The diary just says Lumsden 8am Arnos Grove.

After I had had just enough time to see that the area fell rather short of the classical Arcadia that I had been expecting, Alan drew up. I was immediately struck that he had all those things I hadn’t yet started to think about: a proper job, a sensible house at the end of the Piccadilly Line and a car with an intermittent wiper setting, then a novelty.

The filming would have been the high point of my life so far: my first outing with the Early Music Consort, my first time inside a film studio, rubbing shoulders with Jane Asher and Keith Michell. I was agog. Alan, on the other hand, had seen it all before and having brushed off the costume designer’s offhand “He’ll need a wig” with an insouciant shrug, settled down for the inevitable longueurs with a thick book.

It wasn’t long before I realised that my initial judgment of staid suburban middle age was totally wide of the mark. For a start, Alan turned out to be ferociously well-read, not only the classics of English literature, but French and Russian too, in their original languages. Then I heard of his arbitrage exploits in the Soviet Union. With a music publishing colleague, Richard Pringsheim (the name would have fitted a Bond villain), Alan filled his Ford Consul with cheap Burtons suits, drove east for a couple of days and on arrival in the USSR, would stand up in the marketplace and conduct an impromptu auction. You can imagine the spiel: “Finest wool, latest fashion, just arrived from England”. Pockets stuffed with roubles, they would then drive on to Moscow and refill the car with highly subsidised sheet music of the Russian orchestral repertoire to sell back in London. Alan survived three sorties unscathed, but returned for the last time with a suspended sentence of three years’ hard labour in Siberia hanging over him; Pringsheim, though, was not so lucky: he was once roughed up by police as he filmed the merchandise being snapped up by the good burgers of Smolensk. For a former naval officer (Alan had taken the Russian interpreter’s course during national service, with an automatic commission) to have got up to capers like this at the height of the cold war seemed audacious, foolhardy even. My admiration was beginning to grow.

This was in the seventies, the height of the early music boom. There was an abundance of well-paid work for freelance musicians in London and our paths started to cross more and more. We played together with groups such as The London Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble and Pro Cantione Antiqua, and above all in The Early Music Consort of London and the David Munrow Recorder Consort in their final climactic years. For a while the famous Abbey Road studios became almost a second home. Coming from a rather self-indulgent and amateurish background, I had a steep learning curve to master the sort of professionalism expected by these world-class groups. Alan was my mentor.

Then the memorable day arrived when Alan and Christopher Monk thrust a fine antique serpent into my hands – an instrument that had fascinated me since as a child I saw one in The Observer’s Book of Musical Instruments – and told me to get on with learning to play it.

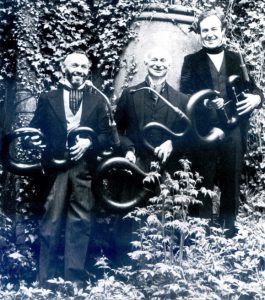

The London Serpent Trio was born shortly afterwards. Our rehearsal sessions, invariably followed by supper in whoever’s house we had met, were always hugely enjoyable occasions with much laughter and silliness. Despite, or perhaps because of, the sheer dottiness of the idea, the group flourished. We all arranged pieces for the group to play and somehow managed to persuade composers including Judith Weir and P D Q Bach (Peter Schikele) to write for us. With the dependable Alan playing the lead part and the engagingly eccentric Christopher Monk as presenter we were greatly in demand under the rubric of ‘something different’; we made three North American tours, numerous European forays, recordings and television appearances. Alan’s love life had always been a bit of a mystery, but one evening when we were playing at a soirée at the Antique Hypermarket in Knightsbridge, he turned up with the stunningly attractive Caroline and introduced her as his fiancée. Then I knew I was in the presence of a master.

As fellow autodidacts, Alan and I shared an enthusiasm for summer schools. After the births of their four children, Alan and Caroline had the bold idea to move from London to a Gloucestershire farmhouse to run as a venue for summer schools and other shorter courses throughout the year. They set me off on my own track by generously inviting me to hold my first four summer schools there in the latter half of the eighties. I was immediately hooked with the idea and soon started to look for a venue of our own, ending up at Lacock in the neighbouring county of Wiltshire, where we ran a summer school for eighteen years.

Thereafter our worlds diverged somewhat. Alan’s main interest was in the early modern era, especially 17th century Italy; my own homed in on renaissance polyphony, a vocal art in which instruments were less called for. Alan and Caroline moved to France and although we would visit from time to time we saw each other less.

Looking back, I realise what a tremendous amount I owe Alan. More than anyone else, Alan was the established professional from whom I learned to survive in the precarious world of freelance music, and the sheer amount of effort you have to put in to do your talents justice. Alan had a capacity for work that I could admire but never match. He was always the loyal and generous colleague who would sometimes tell me truths I would rather not hear, the mark of a true friend. As an entrepreneur, from the boldness of his schemes to his ‘just do it’ management style, Alan was an inspiration and a role model. When we met that wet November morning at Arnos Grove I had no inkling what an influence this new acquaintance would have on my life. My debt is huge.