reprinted from The Independent, 14 May 1998

Dervish Duma, who has died in his ninetieth year, was one of the last survivors from the world of pre-war diplomacy and for sixty years a pre-eminent servant of the Albanian people, as diplomatic representative, wartime broadcaster and unofficial leader of the expatriate community in Britain.

He was born into a land-owning family in the southern coastal village of Borsh in 1908. On 28 November 1912 Albania, the last remaining province of the crumbling Ottoman empire, declared independence from Turkish rule. Her Balkan neighbours, however, had other plans for the territory and in 1913 Borsh was attacked and razed by Greek troops. The family moved to the port of Vlore, where Dervish was enrolled in an Italian school. In 1920 he was transferred as one of the first year’s intake to the new American Technical College in Tirana. English-speaking liberally-educated Albanians were in short supply, and at the age of twenty he was appointed General Secretary of the Royal Albanian Gendarmerie, then under British command. The CO, Major General Sir Jocelyn Percy, recognised Duma’s potential and arranged for him to go to England to study public administration at the LSE from 1933 to 1935.

On his return to Albania, Duma entered the diplomatic service and was given the dual appointment of First Secretary to the Albanian Delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva and Second Secretary to the Albanian Legation in London.

Given that of his two colleagues in London the Minister, Lec Kurti, had a severe visual impairment and did not speak English and the First Secretary was the notorious playboy Chatin Saraçi, Duma’s presence there was valued. Early in 1939 he was made chargé d’affaires. However, on Good Friday of that year Mussolini invaded Albania, declaring it Italy’s Second Overseas Province (the First being Ethiopia). The military logistics of this operation were considerably facilitated by the fact that the Albanian army was being run by Italian advisors. Duma was recalled to Tirana but elected to stay in Britain, where Sir Eric Bowater offered him a job with the paper corporation. He had a long and successful career with Bowaters where his charm, diplomacy and affability were put to good use, particularly in developing and maintaining relations with American publishers.

In 1940 he inaugurated the BBC’s Albanian service. Through his nightly broadcasts he became the voice of hope and freedom for his oppressed countrymen. During the war he also acted as minder to the deposed Albanian ruler, King Zog, who had arrived in London via Greece and Egypt in 1941 and taken up residence in the Ritz Hotel with his wife and entourage of five unmarried sisters. Zog spoke no English and was unaccustomed to western ways. Duma once rescued him trying to buy a packet of cigarettes in Bond Street with a £50 note - over £1,000 in today’s money.

After the war Duma became a leader of the Albanian community in Britain, and through annual visits maintained contact with the sizeable groups that had immigrated to America in the 1920s. At his death he was Chairman of the Anglo-Albanian Association; he had served on its committee for 62 years.

The misery wrought upon Albania under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha brought him much anguish, and he enjoyed a new lease of life after the fall of the communist regime in 1991. He was visited in Surrey by Pjeter Arbnori, Speaker of the Albanian Parliament, and the moderate Kosovar leader Ibrahim Rugova; he saw his son Alexander installed as Honorary Consul in 1992; and was invited to reinaugurate the BBC’s Albanian service it had been closed down under the Wilson government for a paltry yearly saving of £12,000.

Urbane, dapper and immensely charming, Duma was a witty conversationalist and an accomplished raconteur. His Italian, though little used since 1920, remained perfectly pronounced though of limited vocabulary. He was flattered to be taken for a native speaker of the language on a recent visit to Rome. He was a stickler for correct usage in English and Albanian and leaves a body of poetry in both languages.

Andrew van der Beek

reprinted from The Guardian, 18 May 1998

“Perhaps the brightest of the young Albanians here…” ran a wartime Foreign Office memorandum, “a bit of a radical, but basically quite sound”. The subject of this unsolicited testimonial was Dervish Duma, the head of the Albanian Legation in London in 1939, stranded in Britain when Mussolini’s troops deposed the democratic government in Tirana on Good Friday of that year. Duma was one of a handful of liberally educated Albanians who might have been expected to play a prominent part in the governance of his country had democracy been restored. As it was, Enver Hoxha’s hardline communist dictatorship condemned Albania to half a century of stagnation and isolation, and denied Duma a role in the creation of a modern Albanian state.

It might not have been so. In 1949 the British and Americans sent a contingent of specially trained expatriate Albanians to organise opposition to the Hoxha regime (and thus destabilise the whole Soviet bloc). The plan, approved by Ernest Bevin and Dean Acheson, ended in disaster. Many of the Albanians were shot as they parachuted in: others were arrested and killed. The agent coordinating plans between the British and Americans had betrayed the details. His name was Kim Philby.

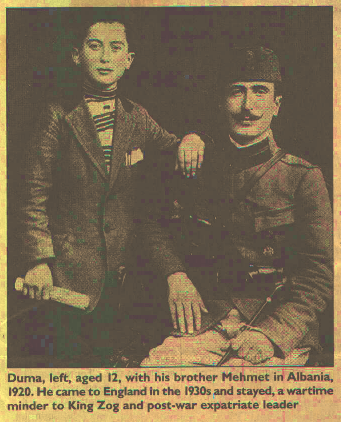

Dervish Duma was born in 1908 in the village of Borsh, on the coast opposite Corfu, to a Tosk land-owning family. Two tragedies marked his childhood: in 1913 Borsh was attacked and razed by Greek troops. Five centuries of Turkish rule had ended a few months earlier; and by the age of ten both his parents had died. In 1920 Dervish was selected to be one of the first year’s intake in the new American Technical College in Tirana. The alumni of this institution came to constitute a much-needed cadre from which the future leadership of the country could be drawn.

After a brief experience in the nascent oil industry, at the age of twenty Duma joined the much respected Royal Albanian Gendarmerie as General Secretary. His abilities so impressed the British CO, Major General Sir Jocelyn Percy, that he made arrangements for Duma to study public administration at the London School of Economics. Duma returned to Albania and entered the diplomatic service. His first appointments were to the League of Nations in Geneva and to London as Second Secretary to the Albanian Legation. Early in 1939 he was promoted to Chargé d’Affaires. However, on 7 April of that year, Italian forces invaded Albania and after heavy fighting, in which the gendarmerie resisted bravely, a fascist government was installed.

Duma saw that he could be of more use to the Albanian people as a free agent in London, and ignored orders to return to Tirana. In 1940 the Foreign Office sponsored an Albanian service of the BBC, with Duma as its presenter. His nightly broadcasts made him the voice of hope and independence for his occupied countrymen. He also continued to help sort out the problems, large and small, of Albanians who found themselves in this country. These included the deposed king, Zog, his wife and son and five unmarried sisters. They had escaped to Greece on the day after the fascist invasion, arrived in London via Egypt in 1941 and were living in some comfort in the Ritz Hotel. Duma often told the story of Zog offering a £50 note (worth a four-figure sum today) to a startled tobacconist in Bond Street to pay for a packet of cigarettes. Luckily Duma was with him and was able to dig in his pockets for the necessary few coppers.

At the outbreak of the Second World War Duma had taken a job with the Bowater Paper Corporation, with which he had a long and successful career. His open and affable personality made him an excellent ambassador for the company and he travelled widely in North America. His annual visits to the USA and Canada enabled him to keep in touch with the Albanian communities that had emigrated there in the 1920s, and with men of letters such as the “great Albanian patriot” Faik Konitza, and the former prime minister and translator of Shakespeare, Archbishop Fan Noli.

Duma also maintained a friendship Edith Durham. She was the indomitable Edwardian traveller in Albania and until her death in 1944 a most vociferous champion of Albanian independence. With Aubrey Herbert she had founded the Anglo-Albanian Association in 1912; Duma was Chairman at his death: he had served on its committee for 62 years.

The fall of the communist regime in 1991 brought Duma a new lease of life. Several prominent Albanians visited him in Surrey to seek his advice. These included the Speaker of the Albanian parliament Pjeter Arbnori and Ibrahim Rugova, the moderate Kosovar leader. The BBC’s Albanian service was resumed in 1993 and Duma was invited to give the first broadcast. He was proud to see his son Alexander appointed Honorary Consul on the resumption of diplomatic relations with Albania in 1992.

Dervish Duma was a man of great charm and an entertaining conversationalist with memories dating back to the Ottoman Empire. His deep love and passionate loyalty for his native land never failed to arouse interest in Albania among all those who met him.

[Andrew van der Beek]

for a fuller article (in German) with many interesting photographs, see Michael Rüegg, Wie Dervish Duma Gesandter eines Königsohne Reich wurde